Second Child Syndrome

This post has been adapted from a 2025 NICAR talk.

I’m the third of four boys. And as any younger sibling may relate: at some point we stumble across our family photo albums and realize: my older siblings each have a photo album … where’s mine? Why don’t I have one?

Such are the diminishing returns in the novelty of having kids: forgetting to document them.

But I am a father of two kids now! Surely, I wouldn’t do the same thing. So I took a look at the data.

Here are the total photos I took of my daughter, six months since her birth … Just over 700 photos.

And here are the total photos I took of my son. It’s half that amount.

Even if we P-hack this a bit … and included photos of my daughter with my son. That brings us to a modest 507 photos over 6 months.

Does that make me bad dad?

What does it say about us when we look at the data we collect, specifically the data I collect on my children?

Welcome to my meta analysis …

Let’s back up a bit and talk about Data. In our practice, collecting data is part in parcel of telling a story.

My daughter was born during the pandemic, so there was a touch of uncertainty. We took that uncertainty (and free time) to channeled it into our kid.

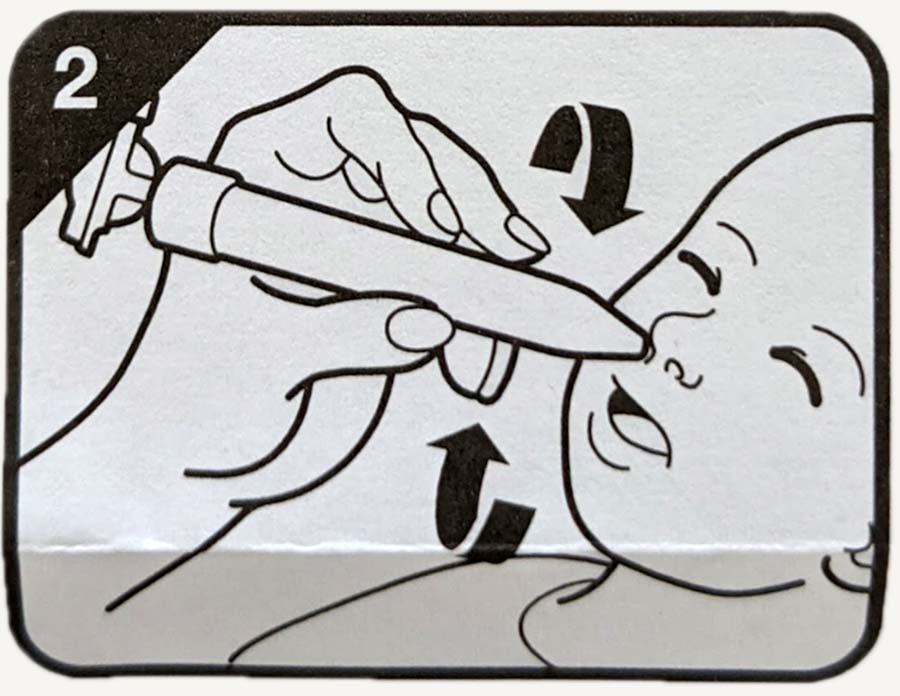

Take feeding our kid. A newborn baby feeds every two to three hours.

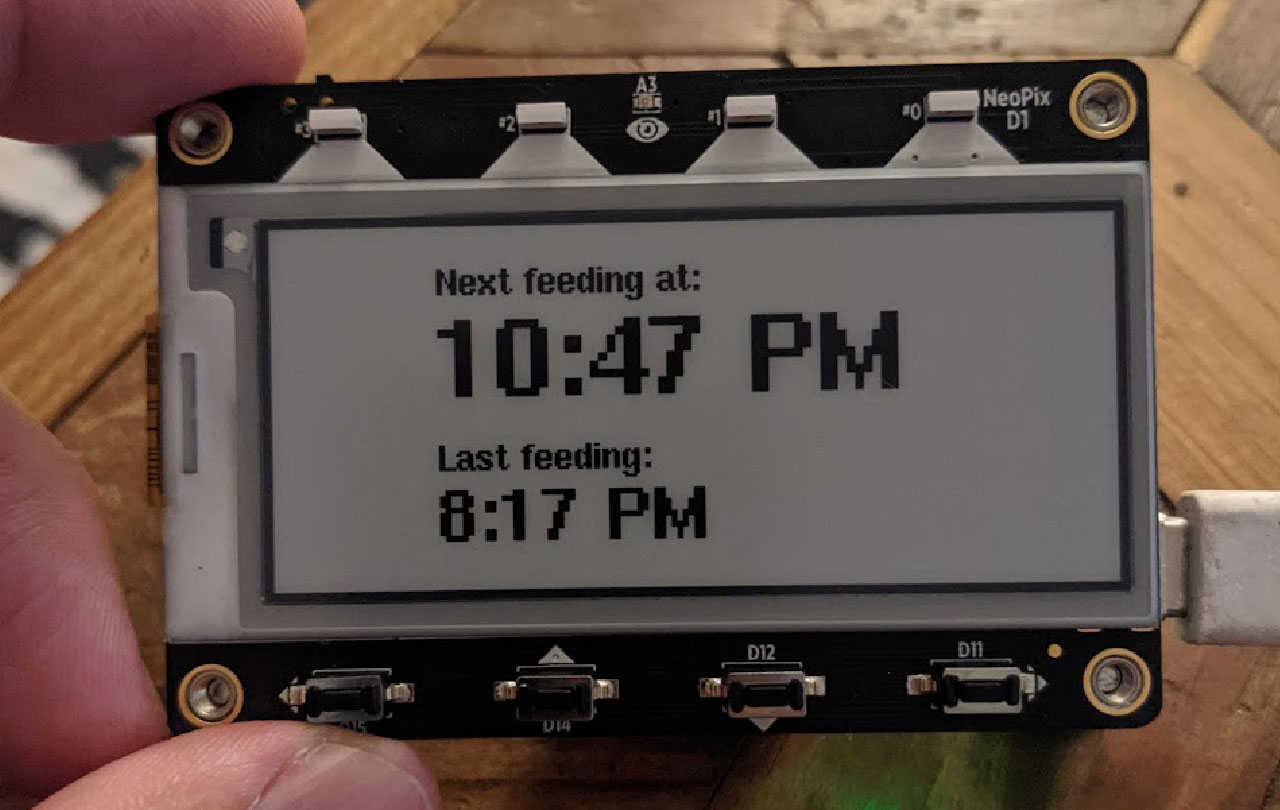

Terrified we’d miss a feeding, we did what any normal parent would do: we setup a database.

With every feeding we used our phones to input the data, an Arduino would take an average of recent feedings and display when to feed our daughter next on a magnetic eInk display we could take anywhere.

This thing was amazing, it didn’t tell us the time, it told us the time to feed.

And I think it helped. Not only in gaining all this data, it soothed our fears we’d starve her.

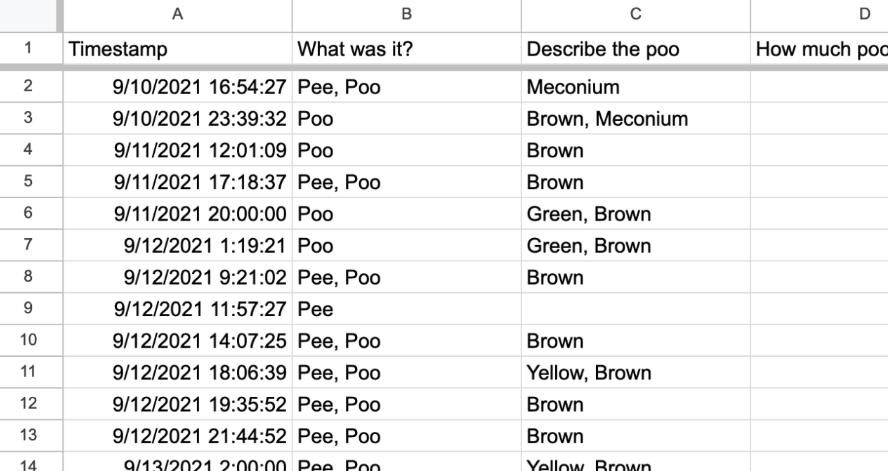

Here’s every feeding down to the minute over a three month period.

Sadly the highlighted circles are bottle feedings, clearly from Mom’s first weekend away.

This informed us to get ME (and him) on the bottle earlier and more often.

A side note: In research for this talk, I had forgotten we even tracked the girls pee’s and poops.

So naturally when our second child was born last June, we would dust off the display and use the API again right?

Readers: We did not use the app.

We moved across the country. We changed jobs. We were raising a two year old (now three year old). And we also had experience!

Look, the baby panopticon is real. There’s no ceiling to what you can record on your kids in this cradle to surveillance state pipeline.

I mean this thing will text you if your baby’s fussing and it costs north of a grand.

At this conference we learn to collect and present data.

In my own life, I think DOING the collecting was a means to satisfy the fear. The fear of missing out, the fear of forgetting, the fear of not being a good dad.

What I think is easy to miss is how things build off one another. We change as we’re challenged with no sleep, bigger family in a struggling industry.

In the end: the kids got fed. They took poops of every hue. The data we collect is just one dimension. And while it’s easy to focus on the delta, as a middle child, I’d encourage you to think of the sum of experiences instead.